THE COURSE

PROJECT IS DUE WEDNESDAY MAY 2 BY NOON

THE COURSE

PROJECT IS DUE WEDNESDAY MAY 2 BY NOON

ABSOLUTE FINAL DUE DATE. Slightly early papers

ARE accepted.

turnitin is up on our Canvas site. It's at the top of

the Assignments folder: Milestone 4

If you have any problems with turnitin, please let me

know ASAP!

PRESENTATIONS ARE SUNDAY APRIL 15 and 22 at 2 AND WEDNESDAY APRIL 18

and 25 12-2. ALL ARE WELCOME!

EDP5285-01 SPRING

2018

PROFESSOR SUSAN CAROL

LOSH

YES! TIME FLIES!

THE FINAL

DUE DATE FOR THE FINAL DRAFT OF THE COURSE PROJECT IS

WEDNESDAY MAY 2 NOON.

THROUGH THE TURNITIN

LINK IN OUR CANVAS ASSIGNMENTS: Milestone 4 SITE

|

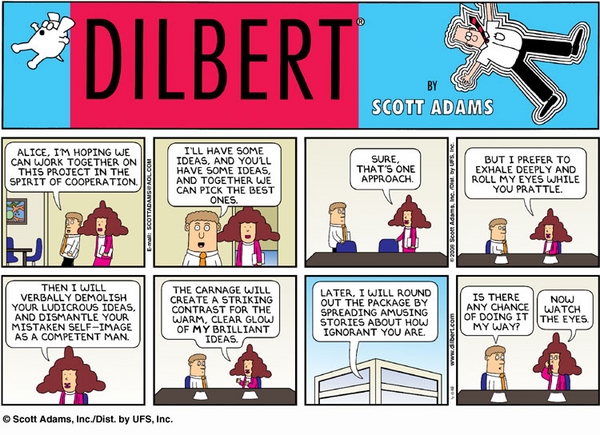

GUIDE TO THE MATERIAL:

TEN

ACROSS, WITHIN: GROUP

COOPERATION AND CONFLICT

|

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

-

Conflict ALSO occurs within groups as well as across groups

-

Internal factions may even split or destroy a group

-

Cross group conflict may occur whether groups anticipate future interaction,

or no interaction

-

When no future interaction anticipated, less of a feeling of accountability

-

Intergroup conflict then can escalate

-

It is much easier to create conflict than to solve cross group conflict

-

Traditional hostilities, scarce resources, strong social identities,

some world views (e.g., "life is a jungle fight")

-

Creating cooperation: what DOESN'T work:

-

Simple contact

-

Contact under enjoyable circumstances (e.g., a movie or banquet)

-

Positive propaganda

-

Creating cooperation: what MIGHT work:

-

Equal status contact

-

Superordinate goals

-

"Jigsaw" problems

-

A problem-solving approach

-

GIVE IT TIME!

-

Cognitive modifiers

-

Stereotypes in particular

-

Resistant to change--a lens to view the world!

-

Ideologically justify cross group conflict and poor treatment of outgroup

-

Groupthink may contribute

-

Social identity may contribute

-

Conflict CAN have positive outcomes for all groups

|

Muzafer Sherif's classic "Robber's

Cave" experiment remains one of the most

famous studies in the group dynamics literature. "Well-adjusted"

White, 11 year old American boys in the mid-1950s had a camp experience

that those who are still around probably remember to this day. They were

brought to camp in two groups and each group was initially separated from

the other. Over several days, each group became aware of the other. In

a matter of days, generously assisted by the research team, cross-group

rivalries developed, culminating in a "tournament." Curiosity gave way

to the development of social identity and in-group loyalty (group names

and symbols) and considerable outgroup animosity. The research team then

faced the task of bringing the two groups peacefully together, which they

eventually accomplished through a series of engineered problems that required

cross-group cooperation to solve.

To this day, I wonder how successful the

research team truly was in creating cooperation--or did they fudge a little

about how much they succeeded? After all, had children gone home prior

to the series of engineered disasters designed to bring the groups together,

what would they have told their parents about the camp experience?

Would the researchers have been sued, despite the signed consent forms?

This series of studies was conducted about 20 years prior to the establishment

of institutional review boards (IRBs or Human Subjects Committees) on campus.

Would they have been approved? What kind of arguments would you have presented

as the Principal Investigator to convince the FSU IRB to approve this research?

WITHIN GROUPS, ACROSS

GROUPS

WHAT KINDS OF DIFFERENCES?

|

Typically we think of conflict as occuring

across

groups and cooperation as occuring within groups. Yet factions and

exploitation can also occur within groups even with as few as three

members, making cooperation among members difficult. At its worse, the

group may become totally dysfunctional and even disintegrate. While we

may at first consider the arguments and conflicts of interest that occur

within informal friendship groups, here are some formal organizational

group examples:

-

About 40 years ago, the large Southern Baptist

Convention (a major USA religious denomination) fractured into what so

far has become three distinct groups, none of which (so far) is quite as

"successful" as the original parent convention. If you hear about "Southern

Baptist pronouncements," these days, you had better be sure which

Southern Baptists are meant.

-

Academic college departments often split in

two (or more), and sometimes an entire department may either cease to exist

or may be subsumed by another department. Educational Policy at FSU was

once part of the Department of Educational Research (now Educational Psychology

and Learning Systems), then its own department of Educational Foundations,

and is now part of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy

Studies (can you keep this one straight without a scorecard?)

-

Corporations may become so internally fractured

that the company goes out of business, such as the family owned former

Pic N'Save stores in North Florida, whose family members simply could not

agree on how to run the business after their parents died. (They went into

bankrupcy and never came out.)

On the flip side, groups may have a history

of intermittent or regular intergroup cooperation. The National Council

of Churches encouraged working relationships among several liberal to moderate

interpretive Christian denominations. Colleges and universities agree to

have regular schedules of sports competition with each other in leagues.

Neighborhoods may cooperate in "fighting City Hall" on urban development.

| ANTICIPATED VERSUS UNANTICIPATED

CONTACT |

While continued competitive interactions

may create conflict, many consequences probably depend on whether these

competitions are within or across groups, and whether these competitions

are regularized in some way. Internal competition may be detrimental

to group cohesion and lead to members resenting one another. In classrooms,

we see this in the use of strict "curves" for grading. " Win-lose" evaluations

(zero-sum matrices) or rating systems in employment and other group endeavors

can sometimes even lead to the sabotage of others' efforts or "colleagues"

denigrating the efforts of their peers.

Although one might suppose that internal

conflict might be greater under conditions of scarce resources (see below),

some recent research has found it is the rankings and relative proportions

that matter to many members (about 1/4)--even if the total payoff is less

for individual group members.

On the other hand, what about teams which

play each other on a regular basis, where competition is expected, or "traditional

rivalries" such as "brain bowls?" (Or the Seminoles versus the Gators.)

Corporations, too, are regularly ranked by several agencies. Perhaps surprisingly,

competition can be "good-natured" as well as "cutthroat."

The Johnsons suggest that a "go for the

win" strategy or distributed negotiation is

most pronounced when parties do not regularly interact and do not anticipate

future interaction. Under these circumstances groups do not see mutual

interests and may believe that their own negative actions will not have

consequences. On the other hand, integrative negotiation,

or problem solving attempts to maximize joint benefits should be more common

when regular interaction is expected. For example, football teams from

adjacent high schools, whose members interact in several other contexts,

may still want to win but may also be less likely to engage in truly "dirty"

ploys. Supportive evidence has been reported in summaries by sociologist

Joe Feagin. In another example, the FSU faculty union (United Faculty of

Florida-FSU) uses "interest based bargaining" or shared interests in collective

bargaining with the FSU administration.

For whatever reasons, it appears much

easier to create conflict among groups than to create cooperation.

Here are some factors that increase animosity across groups:

-

Competition for scarce

resources. Competition can create conflict both within and across

groups.

Within

groups, individual interests may be at odds with group interests, especially

in the short term. "The tragedy of the commons"

refers to the tendency of individuals in search of their own interests

to deplete group resources faster than they can be replenished. Ultimately

all

group members, including those who initially profited,

are far worse off.

It doesn't take much. For most of us much

of the time, resources are short and desirable resources are always

short. A tight job market, a selective graduate program, a desirable place

to live, next to no raise money, the "big game": free market economists

claim competition is supposed to "bring out the best in us." Competition

is supposed to make us sharper and more productive. It can.

But instead competition, especially fierce

competition, can also generate sabotage, scapegoating, and conflict

across groups that damages overall productivity. That said, competition

theories do not tell us

which groups will be scapegoats, what the

outcomes are likely to be under which circumstances, or whether the target

will be groups rather than random (or lucky) individuals.

Competition appears

to interact with:

-

A cultural history

of hostilities. Whether

competition among groups which have lived close to each other creates hostilities,

or whether the rancor created by long-standing stereotypes provides a convenient

target for aggression, outgroups, in fact, are seldom random. Outgroups

tend to be low enough in social standing that negative actions taken against

them are not met with swift punishment or enforced restraint from legitimate

authorities or powerful allies. Groups appear to agree on the rank order

standing of each other in society (exempting one's own group, see below).

Identifiable

groups low in power and resources often become scapegoats for

many of the groups ranking above them. Sociologists refer to the intersection

of race-gender-class to designate groups that may be particularly vulnerable.

However, sexual orientation and sexual preference are clearly also factors,

as can be religion.

Skin color or shape, distinctive clothing

or head gear, symbols (e.g., a cross or a star) can make a group member

relatively easy to identify, although mistakes are common. Asian

Indians are more likely to wear a turban. for example, than middle Easterners,

e.g., Saudis, which many U.S. adults do not know. Many USA Jewish Community

Centers have Christian members.

Within groups, too, there is often

a rank order. Departments within a school or a college may be unobtrusively

rated by their fellows in social status. Fraternities may rate women as

acceptable dating partners or as sexual fodder (work by Mindy Stombler

and Patricia Martin). Members of various standing in the military rate

the other services--and platoons of their own.

-

Ingroup solidarity.

When

groups are internally very cohesive (especially on the interpersonal dimension),

they tend to be less friendly toward other groups. This may occur because

high levels of internal cohesion exist (review Groupthink!).

-

Accentuate social

identity. When individuals

identify very strongly with a group, they are less friendly toward other

groups. You may be surprised to learn how trivially easy it can be to activate

social identity. Remember studies early in the semester that found a student's

pain tolerance greatly increased if you told him/her that "Catholics [Jews/fill-in-the-blank]

tolerate pain less well than other religious groups." Cultural symbolism

(flags, songs, photos, mottos, sports insignia, which plentifully occur

in many groups) also activates social identity.

-

Diversity.

Differences

in personal styles (e.g., authoritarianism), gender or ethnicity (different

background experiences leading to different expectations), or power differentials

can also increase the potential for within or cross group conflict. This

is particularly the case if there is fusion across different levels,

for example, power differentials coincide with gender. Lower status members

will be distrustful and higher status members tend to over-estimate their

contributions to a group.

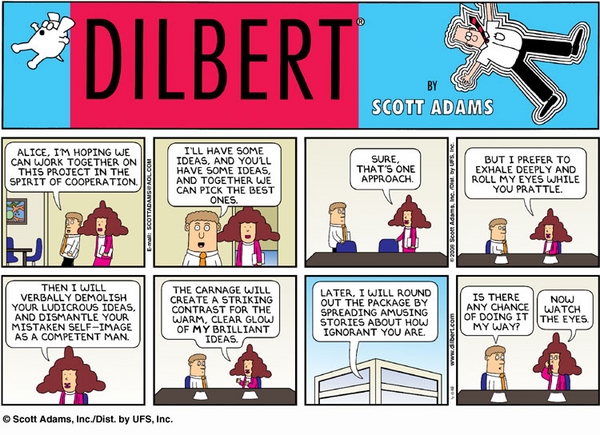

Are some people particularly prone to create

or aggrevate group conflict? Lawrence Wrightman's

philosphies of human nature refer to individuals who see the

world as an untrustworthy place. Such individuals tend to go into situations

with a "win-lose" perspective rather than a focus on shared problem solving.

Of course, unwittingly, these "jungle fighters" can create the very competitive

and abrasive situations that they claim to find so abhorrent. Others react

to these dominance attempts and what is easily perceived as outright GREED

with escalated competition and rancor--and the battle is on. Unfortunately,

Prisoner's

Dilemma Game studies indicate that it is easier to lose trust

and create competitive situations than it is to create cooperative relationships.

Once

lost, trust is not easily regained.

Unfortunately, it is tougher to create

cooperation than conflict. If one approach does not work, the advice is:

try, try again with something else. Keep in mind that adversarial parties

in conflict often

don't want to meet, don't want to cooperate.

In an atmosphere of suspicion, each side fears that any attempts at reconciliation

will be seen as weakness or concessions, leading the "advance party" worse

off than before.

-

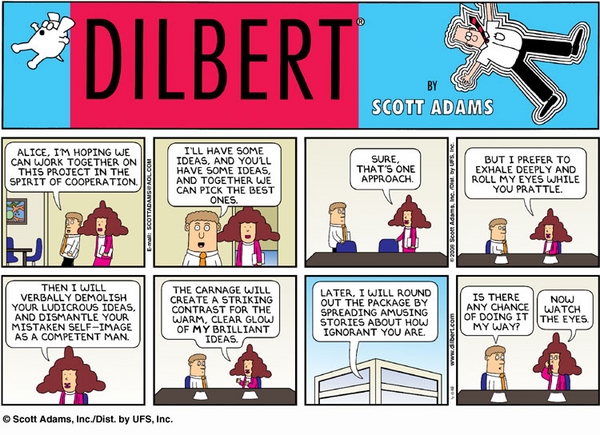

Simple contact.

The

idea that we can simply put together different factions, ethnic groups,

gangs, or other "warring" entities in the same room, the same school, or

the same neighborhood is popular. Too bad. Not only do groups rarely

become more positive toward each other, simple contact appears augmented

by selective perception and stereotypes. What happens next is that

groups typically become

more hostile toward one another. Contact

is seen as the excuse to fuel negative impressions (the Israeli-Palestinian

situation provides some vivid examples of this).

Part of the problem is that simple group contact

is often stratified or unequal contact.

For

example, when largely White schools are integrated with Hispanic or Black

students, Whites are more often placed into Honors classes, and the Hispanic

or Black kids, originally from schools with fewer resources, are placed

in remedial courses. Thus, White students and their parents look around

to see their worst ethnic stereotypes reaffirmed and vice-versa. Anything

that segregates a particular group and makes it visible (e.g., "Women's

Auxilliaries") will not create more positive cross-group attitudes. Recall,

after all, that Southern Whites and Blacks interacted for years--but not

as status equals.

-

Contact under pleasant

circumstances. Perhaps simple

reinforcement theories could work, so the somewhat simple-minded theory

goes. We place "warring factions" together to enjoy a pleasant experience

such as a meal or a movie. Sad to say, that typically does not promote

cooperation either. In fact, the occasion may provide the opportunity

for rival groups to call each other names, "gather more dirt," or even

throw food as the Robber's Cave campers did in the cafeteria during

the Sherif experiments.

-

Provide positive

information about the other group. Group

members don't pay much attention, remember very little, and are highly

skeptical about what they do remember. It probably won't hurt, but

providing "positive propaganda" about a warring group probably won't help

much either.

Try some of these suggestions and remember

to give any of them some time. It's easier to instill suspicion

than trust (repeat!).

-

Contact must be equal

(or even higher) status. Rival

or hostile groups must meet as status equals in the task at hand. It may

be difficult to convince group members that the other group is equal overall,

but information must be given at the beginning that these groups are equal

with respect to the task. The "imagined" member of an "outgroup" is

presented as high status, popular or a prizewinner.

-

For several years, the National Science Foundation

has been very concerned about the paucity of women and Black or Hispanic

minorities in certain science fields (e.g., physics). Some of the studies

they funded have visited college campuses to conduct in-depth interviews

with faculty, staff, and administration. One conclusion the NSF has drawn

is that inclusion MUST "begin at the top." If

top university and college administration appear to support inclusion,

the result is an increase in women/minority doctorates awarded, in diverse

faculty, and in administration. If support at the top appears lukewarm

or non-existent, not much gets done. This approach appears especially pertinent

to hierarchical organizations. Consider analyzing this approach in other

institutions, such as politics.

-

Superordinate goals.

This

was the most famous conclusion to emerge from the "Robber's Cave" studies.

The researchers created a series of disasters that required cooperation

from all campers, Rattler and Eagle alike, to solve. For example,

the "water pump broke," then the truck "broke down." Both Rattlers and

Eagles had to retrieve the necessary parts.

-

A variation on superordinate goals is Aronson's

(senior and junior...Elliot and Josh)

Jigsaw Classroom.

Aronson

and his colleagues created multidimensional tasks and integrated groups.

Each child received one piece "of the puzzle" and had to teach other students

in the group. Only when all group members contributed and cooperated could

the entire group complete the task. This approach has now been used in

school systems all over the United States and is one large portion of a

greater approach that has come to be called cooperative learning.

-

Take a problem solving

approach. Integrative negotiations

are more likely to result in cooperation than distribution negotiations

in which people try to maximize payoffs. A focus on what group members

(or groups) have in common as well as defining conflict as localized helps

to mediate disagreement. Very often, groups "at war" still have

common problems. Interest-based collective bargaining is one example.

For example, we all must live on the

same Earth. All of us, no matter how rich or poor, are possible victims

of SARS, the contagious respiratory virus that periodically erupted beginning

in 2003 (in fact, the initial victims have tended to be the poor, living

under unhealthy and crowded conditions--or the "rich" who could afford

to visit Hong Kong or Singapore from Western countries) or avian flu--or

this year, even measles, mumps or whooping cough. Clearly, there will be

disagreements. Is there "really" a global warming problem? Is avian flu

a new contagious virus that could create a pandemic? Opposing sides will

war about the definition of the problem, whether there

is a problem,

and what to do about the problem. In the process, we can only hope that

each side will see common goals and decide to cooperate.

-

Give it time.

Aronson

(and others) have found that students are initially hostile to members

of other ethnic or gender groups. It can take several weeks of working

together productively to produce more positive views toward the other group

and more interaction. Remember that if we can get diverse members to work

together in the first place, diverse groups are more productive and creative.

|

IN-GROUP AND OUT-GROUP COGNITIVE

PROCESSES

|

Several cognitive processes can foster

cross-group conflict.

-

The social perception literature tells us

that we tend to remember vivid information and

information

more consistent with existing cognitive structures more easily.

All

it takes is one vivid incident about an individual or

group ("did you hear what happened in the Anthropology parking lot last

week?") and that information tends to be remembered and generalized.

-

In our private lives, we tend to "affirm

the consequent," that is, we are "agenda scholars": we draw

conclusions first, then search for supportive evidence. If, for example,

I tell you that someone was born under a particular zodiac sign (say, "The

Year of the Dragon" or a "Leo"), you will tend to select, accentuate, and

remember information that is consistent with your schema, or cognitive

picture, of a "Dragon" or a "Leo."

-

The Fundamental Attribution

Error. Research indicates

that we are more likely to attribute our own actions to the environment,

the situation, or other people while we explain the actions of others

in terms of their personal characteristics or dispositions. This sets the

stage to interpret actions performed by others as due to intended

and personally driven malice or hostility. Sound familiar in today's heated

political environment?

These processes can unwittingly support cross-group

conflict. But probably the most studied cognitive phenomenon with respect

to intergroup relations is stereotyping. Stereotypes

are a special type of cognitive prototype applied to large social groups.

When we stereotype, we

categorize. We take the

people we encounter and place them in a "cognitive bin" with information

about other people whom we believe are similar in key respects (such as

gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, occupation or age). This is all

well and good--people categorize all kinds of objects as a form of cognitive

"economy" (do you examine every head of lettuce at the store? or each tube

of Colgate toothpaste?). However, stereotypes differ in key sinister ways

from other forms of categorization:

-

Stereotypes reduce

outgroup variation. Members

are seen as more alike than they really are (for example, stereotypes about

memory loss in older people).

-

Stereotypes exaggerate

differences between the ingroup and the outgroup. For

example, stereotyped individuals will argue that "men are logical and women

are emotional" (or "men are from Mars and women are from Venus"...)

-

Stereotypes tend

to be rigid. When presented

with contradictory information about other kinds of objects, people tend

to alter their generalizations, at least to some degree. However, we are

more likely to defend our stereotypes, claiming the contradictory

information is "the exception that proves the rule" or that "most 'Xers'

fit the mold." This rigidity suggests that individuals have a kind of vested

interest in believing their stereotypes are true. Probably so, since:

-

Stereotypes typically

rank groups in a social hierarchy or stratification system.

No

surprise! Ingroups tend to be ranked higher, outgroups ranked lower. The

interesting thing is that it is largely rankings of the ingroups that

are the most distorted compared with the rankings of others. One study

of sororities at Tulane University in New Orleans found that "sisters"

nearly always rated their own sorority at the top of the list. Their rankings

of the other sororities were closely tied to rankings given across campus

(with the exception of each woman's own sorority, of course).

-

Stereotypes ideologically

justify poor treatment of the outgroup. Members of the ingroup

carefully explain the necessity for their condescending, segregating, even

cruel or violent, behavior toward outgroups. They must badly

treat outgroup members in these ways because outgroup members behave in

such shabby, incompetent, even dangerous ways. The cause of the hostilities

is attributed to the outgroup. Group members may believe that an outgroup

is so threatening that they must engage in "pre-emptive strikes," damaging

the outgroup sufficiently so as to prevent harm to themselves. For example,

Jim Jones' actions in Jonestown in shooting and killing visiting politicians

from the United States decades ago were justified to the group by explaining

that the politicians had come to harm Jones and the Jonestown community.

|

THE ROLE OF COGNITION: CAUSE

OR CONSEQUENCE?

|

Psychology typically locates the genus

of action in the individual. Thus, psychologists will treat stereotypes

and other ideological factors held by individuals as causal to outgroup

hostility and scapegoating. Social psychologists recognize that

some causes of our behavior are internal but that others emanate from the

environment. Further, social psychology has shown that if people change

their behavior (perhaps due to outside forces) and feel committed to that

behavior, attitudes will often follow suit to become consistent with the

behavior.

What does all this mean for the rhetoric

of outgroup hostilities? Some conflictual actions toward outgroups

no doubt occur because we hold pre-existing negative attitudes toward a

particular group. However, it is also possible that because we treat

members of a group poorly, we develop hostile attitudes toward them.

To admit that we engaged in aggression toward members of another group

(including cheating at games, stealing possessions, or even murder) because

we were jealous, coveted their resources, felt bad because we had failed

at something, or wanted an advantage toward some type of prize could induce

considerable shame, guilt and anxiety. To ameliorate these nasty feelings,

we convince ourselves that members of the other group "deserve it" because

of their derogatory characteristics. Thus, we feel better about ourselves

and our actions. We may even glorify ill behavior toward outgroups, convincing

ourselves that "society is better off."

Once again we return to the combination

of strong interpersonal cohesion and highly directive leadership that can

produce "Groupthink." Several elements that Irving Janis idenitified in

the syndrome were cognitive characteristics: heightened in-group identification;

"we-they" thinking; a tendency to denigrate other groups and to see them

as inferior to one's own. One's own group was seen as relatively invulnerable.

This perspective is also endorsed by many

social identity theorists.

One guilty party that contributes so much

of the research in this section is a strong sense of group identity. Is

cross-group antagonism inevitable? Some social and behavior scientists

think that this is so, because competition constantly occurs for valued

and scarce goods. On the other hand, insights from game theory and negotiating

suggest cautious optimism. By changing the definition of the situation,

we may be able to maintain cohesive groups yet minimize outgroup hostility.

|

A SIDE BAR FROM GAME THEORY

|

Game theorists (e.g., The Prisoner's Dilemma)

work with a variety of "payoff matrices"

to

study how groups and individuals interact. In "zero-sum"

games, what one person or group wins, the other loses. This

is true in most team sports, wherein only one team can win the game

or the tournament. However, zero-sum is not necessarily the case in individual

sports such as marathon running, where players are relatively satisfied

if they set a "personal best."

In non-zero-sum

games, it is possible for all parties to win something,

although the payoffs may vary to the different groups. Although the naive

outsiders often believe that labor and management wage constant war, in

fact unions provide a structured and ritualized bargaining situation for

both union and administration to "come to the table." Under these circumstances,

agreements may be hammered out so that both parties believe they have gained.

Superordinate goals tend to create non-zero-sum games.

Of course, so much depends on the relative

resources of all parties to the interaction. If a group holds few bargaining

chips, there is little incentive for the more powerful group to bargain.

The less powerful group may be able to appeal to altruism or to guilt over

prior treatment. Less powerful groups may be able to form

coalitions (for example, the "Tea Party" with the economically

conservative among Republicans, and minorities and working class of diverse

ethnic backgrounds among Democrats) thus making them more equal to groups

holding more resources.

Research from some bargaining studies suggests

that for as many as 25% of us, what counts is "doing better" than others--even

if everyone is worse off. It's still unclear what predicts individuals

who take this kind of unproductive stance.

Finally, it is important to remember that,

although conflict is typically treated as destructive and to be avoided,

it can be positive for groups. One does not necessary have to take the

Johnsons' position that conflict prevents life from getting boring! (Sometimes

boring has a lot of appeal.) Whether across or between groups, conflict

can:

-

Lead to the development of skills

-

Strengthen group identity

-

Lead to cross-communication across groups

that might not occur otherwise

-

Develop negotiating skills

-

Foster the use of compromise

-

Ultimately force groups to cooperate for their

own mutual benefit

This page was built with

Netscape Composer.

Susan Carol Losh April 14

2018

THE COURSE

PROJECT IS DUE WEDNESDAY MAY 2 BY NOON

THE COURSE

PROJECT IS DUE WEDNESDAY MAY 2 BY NOON