WILL YOU GATHER DATA THIS SEMESTER (on people--even secondary analysis)? IF YES, CALL THE FSU'S HUMAN SUBJECTS COMMITTEE. CLICK HERE .

| OVERVIEW |

WILL YOU GATHER DATA THIS SEMESTER (on people--even secondary analysis)? IF YES, CALL THE FSU'S HUMAN SUBJECTS COMMITTEE. CLICK HERE . |

|

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

|

SYP 5105-01 FALL 2017

| THEORIES

OF SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

SUSAN CAROL LOSH |

|

ISSUES IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY METHODS |

|

METHODS |

VALIDITY |

METHODS |

DISADVANTAGES |

Regardless of disciplinary department home, most social psychologists are empiricists, that is, we test our conceptually-derived hypotheses with systematically gathered data. If the data contradict or disconfirm our hypotheses, then typically we revise and retest the theory. On the other hand, social psychologists are eclectic. Most of us use a variety of methods, such as experiments or surveys or focus groups, depending on the topic at hand. While it is true that psychologists are relatively more likely to use experimental methods and sociologists are relatively more likely to use surveys, ethnographies, or observational methods, all of us in social psychology tend to select methods that depend on the kind of research questions we ask and the research topics that we choose.

Here are some personal examples.

What

if your participants can't talk? Check out some ingenious canine experiments

(not mine) HERE

(optional)

Last year, a Hungarian

study trained dogs to climb into an MRI machine and lay motionless

for 8 minutes to see brain responses to food versus one's humans!

What

if your participants can't talk? Check out some ingenious canine experiments

(not mine) HERE

(optional)

Last year, a Hungarian

study trained dogs to climb into an MRI machine and lay motionless

for 8 minutes to see brain responses to food versus one's humans!

|

|

Causality is critical to the research enterprise. Much of the research process centers around designating the "true causal" or “independent variables.” What we initially may consider to be “true causal” variables may, instead, turn out to be artifacts of the research process (e.g., evaluation apprehension in response to being an experimental subject), the particular group that we studied (college undergraduates at research universities), or thinking that we had measured variable one while we had, in fact, studied variable two ("response set" format on psychological tests instead of any actual content) . A great deal of behavioral science consists of ruling out alternative causes or explanations. Because experiments (especially with college students) often suffer from phenomena such as evaluation apprehension, reactance, or social desirability, and have problems with generalizing (external validity) it is incorrect to assume that experments are the "only way" to study causal forces.

Establishing causality is by no means agreed-upon even among scientists, let alone most members of a particular culture. If you subscribe, at least in part to the "rational laws" approach, you also probably accept controlled experiments, logic, "reasonable arguments,” and statistical control as suggestive of "proof." Science is one form of knowing and one generic way of gathering evidence that either disconfirms or suggests causality.

According to science rules, definitive

proof via empirical testing does not exist. Science uses the term "proof"

(or, rather, "disproof") differently from the way attorneys or journalists

do. Our measurements could be later shown to be contaminated. A correlation

could have many causes, only some of which have been identified. Later

work can show earlier causes to be spurious, that is, both supposed cause

and effect depend on some prior causal (often extraneous) variable. Statistics

are

NEVER EVER considered to "prove" anything (neither do experiments)

although statistical results CAN disconfirm or "support". It sounds overly

tentative but in fact is simply the cautious voice of science experience.

|

|

In order to make any causal assessments in your research situation, you must have reliable measures, i.e., (in part) stable measures. If the random error variation in your measurements is so large that there is almost no stability in your measures, you can't explain anything. Picture an intelligence test where an individual's scores ranged from developmentally challenged to genius level over a short period of time. No one would place any faith in the results of such a "test" because the person's scores were so unstable or unreliable.

Reliability is a necessary but not sufficient condition to make statements about validity. Reliable measures could be biased and hence "untrue" measures of a phenomenon) or confounded with other factors such as acquiescence response set. Picture a scale that always weighs five pounds too light*. The results could be reliable, but they would be inaccurate or biased because they deviate from the true expected population value, in this case, your "true" weight. Or, picture an intelligence test on which men or people of color always score lower (even if this doesn't occur on other tests). Again, the measure may be reliable but biased.

(*we rarely hear about the personal scale that consistently weighs 5 pounds too heavy)

Internal Validity

Internal validity addresses the "true" causes of the outcomes that you observed in your study. Strong internal validity means that you not only have reliable measures of your independent and dependent variables BUT a strong justification that causally links your independent variables to your dependent variables. At the same time, you can rule out extraneous variables, or alternative, often unanticipated, causes for your dependent variables. Thus strong internal validity refers to the unambiguous assignment of effects to causes. Internal validity is about causal control.

Laboratory "true experiments" have the potential to make very strong causal control statements. Random assignment of participants to treatment groups (see below) rules out many threats to internal validity. Furthermore, the lab is a controlled setting, very often the experimenter's "stage." If the researcher is careful, nothing will be in the laboratory setting that the researcher did not place there. When we leave the lab to do studies in natural settings, we can still do random assignment of participants to treatments, but we lose control over potential causal variables in the study setting (dogs bark, telephones ring, the experimental confederate just got run over walking against the "don't walk" sign on Stadium Drive.)

External Validity

External validity addresses the ability to generalize your study to other people and to other situations. To have strong external validity (ideally), you need a probability sample of participants or respondents drawn using "chance methods" from a clearly defined population (all registered students at Florida State University, for example). Ideally, you will have a good sample of groups (e.g., classes at all ability levels). You will have a sample of measurements and situations (you study who follows the confederate who violates the "don't walk" sign on Tennessee Street at different times of day, different days, and you also employ different locations on campus.) When you have strong external validity, you can generalize to other people and situations with greater confidence.

More attention is typically paid to the

sample of participants but the sample of situations is also important.

For example, few of us in "everyday life" are asked to shock another person

in a "learning experiment". The later work of Stanley Milgram and others,

e.g., asking subway passengers to "give up" their seats or individuals

dressed in blue with gold braid asking students to "put a nickel" in the

parking meter in college parking lots, lend more verisimilitude to Milgram's

initial experiments on "obedience."

|

|

Each major method that social psychologists use has its advantages and disadvantages. A certain method may work better to study some areas than others. For example, it is critical to assess whether you are studying individuals or groups. A method that can work well to study individuals, such as a survey questionnaire, can work poorly to study groups.

EXPERIMENTS

Lab participants also typically have too similar backgrounds (e.g., college students or military recruits are about the same age and the same educational level). Thus both the sample of participants AND situations may be too limited to allow high external validity.

Lab experiments are reactive (obtrusive). Generally, participants are acutely aware that their behavior is under scrutiny. They may react with anxiety (evaluation apprehension), with the desire to "fake" good (social desirability) and appear smarter, more attractive, or more tolerant than they typically are in their everyday behavior.

It's a good idea to use a manipulation check to be sure that on some level the participants noticed the experimental treatment. If you manipulate a variable and the different treatments never register, the treatment probably won't make a difference. For example, if you use a "buddy system" in a stop-smoking group, we would expect the subjects to rate the group as friendlier than subjects who don't receive the "buddy system" treatment.

Field experiments

Public opinion

SURVEYS typically

take REPRESENTATIVE PROBABILITY SAMPLES thus

have relatively high external validity for participants.

In

surveys, questions are asked and the answers are recorded, sometimes by

interviewers, sometimes using paper-and-pencil questionnaires, and sometimes

robotically by touching your keypad.

|

One form of secondary analysis involves archives. Secondary analysis data were gathered for purposes other than the current study, such as government statistics or marketing. For example, currently, I am analyzing data on basic science knowledge from the National Science Foundation Surveys of Public Understanding of Science and Technology. There are over 40,000 interviews spread over 13 surveys conducted between 1979 and 2016.. The General Social Survey spans 1972 to 2016 and contains literally hundreds of different attitude measures as well as demographics. Much of it is available for online analysis.

It is incorrect to assert, as some research methods textbooks do, that internal validity or causal control can only be accomplished through experiments. Browse through the American Educational Research Association's excellent book about establishing causality in observational and survey designs of various kinds (optional but you can download the pdf of this book FREE) HERE.

Researchers may use content analysis to study media or other documents. For example, you might study gender stereotypes in sports magazines or the frequency of unmarried couples cohabiting on television situation comedies. Causal control is low but mundane reality can be high. External validity can be high with careful sampling. Content analysis has been cautiously combined with surveys to show how watching television can influence adult attitudes and behaviors (such as "The Mean World Syndrome").

Simulations occur in constructed settings. Participants may role play or act "as if" they held certain roles such as a parent, a prison guard or head of state. A classic example is the Haney, Banks and Zimbardo prison study, which was both a simulation and an experiment; you can access an optional slide show of this study at Philip Zimbardo's web site HERE.

|

|

The chart below synopsizes relative advantages and disadvantages of each method. Notice that a strength for one method, such as strong internal validity for laboratory experiments, is often balanced by a weak point, such as the limited external validity in many laboratory experiments because of the reliance on "captive" participants such as undergraduate college students or military recruits. This means that the wise researcher will use a variety of methods. When different methods to study the same phenomenon produce comparable results, we call this triangulation. Carefully consider the evidence in the studies that you read about, both in your assigned readings and also when you review articles and other readings for your course project, for example:

THE UNIT: Since we study individuals, but we also study groups and organizations, it is imperative to make your measures consistent with the unit you have chosen.

THE TIME FACTOR: Because some results fade quickly (e.g., your specific attitudes about almost anything political, including presidential election choice) and others are "sleepers" or increase over time, you should assess whether followup over time was needed--and whether it was done.

REACTIVITY: A classic social psychology study found that simply viewing oneself in a mirror changed behavior. Picture, then, the effects of being in a research study! Was there any control for reactivity (changing your behavior because you believe you are being studied)? Sometimes that does mean we must use deception in experiments. After all, if you told people "this experiment is to assess your attractiveness," we can be pretty sure that people would immediately "up their image."

NOTE: The chart below refers to the "usual" or "typical" professional study. Any specific study, of course, may be "better" or "worse".

ALPHABETIC ABBREVIATION

IN CHART BELOWTYPE OF METHOD A Laboratory Experiments B Field Experiments C Participant Observation (often ethnographic) D Field Observations E Surveys F Secondary Analysis G Simulations H "Natural" Experiments

| METHOD |

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

| Causal

Control

(Internal Validity) |

Excellent | Fair

to

Very Good |

Fair to Good | Fair | Fair to Good | Fair | Can

be

Good |

Poor |

| Control over Other Factors | Good | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Can

be

Good |

Poor |

| Represents

Population

(External Validity) |

Often Poor | Fair to Good | Fair to Good | Fair | Very Good | Can be Good | Poor | Varies |

| Time Follow-up | Often Poor | Very Poor | Good | Fair | Can be Good | Can be Good | Poor | Can

be

Good |

| Mundane Reality | Often Low | High | High | High | Fair to High | Varies | Low | High |

| Reactivity | Often High | Low | Middle | Middle | MAY be high | Low | High | Low |

| Unit of Study | Person or Group | Person or Group | Group | Person or Group | Person | ** | Person

or

Group |

Often Group |

**Varies with the original method of collecting data which is specific to each research study. For example, the unit may be a person, a group, a cultural reproduction such as a television show or magazine, or a created cohort.

And of course, just because a particular

method "can be" good, that doesn't mean a particular study, in fact,

has that specific strength.

| OVERVIEW |

|

|

This page was built with

the late lamented Netscape Composer.

Susan Carol Losh August

28 2017

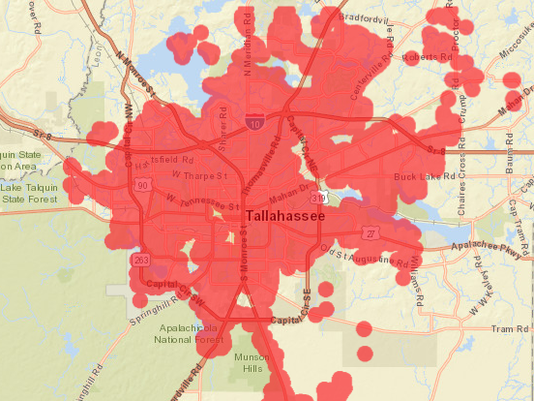

New Orleans September 2005 Lights out Tallahassee2016

Houston Texas August 28 2017